The Mughal dynasty (1526–1858) was among the richest and longest ruling in India, and at its peak controlled large portions of the Indian subcontinent. The Mughals were Muslims of Central Asian origin, and Persian was their court language. Their intermarriage with Hindu royalty and establishment of strong alliances with the diverse peoples of the subcontinent led to profound cultural, artistic, and linguistic exchanges.

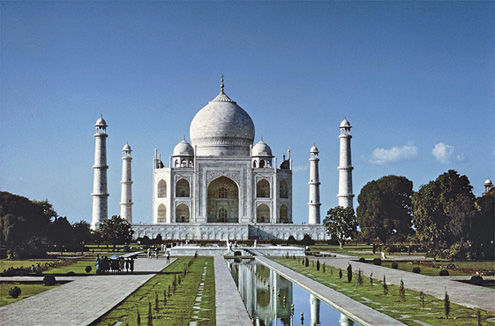

The Mughal dynasty claimed descent from the Mongols ("Mughal" is from the Arabized transliteration of "Moghol," or Mongol). The Mughal emperors were among India's greatest patrons of art, responsible for some of the country's most spectacular monuments, like the palaces at Delhi, Agra, and Lahore (in present-day Pakistan) and the famous mausoleum, the Taj Mahal (fig. 28).

Fig. 28. Taj Mahal, Agra, India, 1632–53. Commissioned by Shah Jahan

The tastes and patronage of the first six rulers, known as the Great Mughals, defined Mughal art and architecture, and their influence has endured to this day. The works of art featured in this chapter highlight artistic production during the reigns of Jahangir (1605–27) and his son Shah Jahan (1627–58).

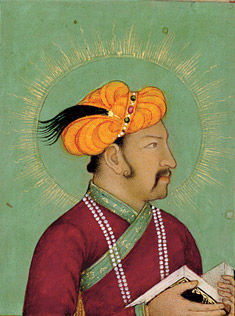

Fig. 29. Portrait of Jahangir (detail), about 1615–20; India; ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; 14 x 9 1/2 in. (35.6 x 24.1cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913 (13.228.47)

Emperor Jahangir (fig. 29) remains best known as a connoisseur and patron of the arts. His memoirs, the Tuzuk-i Jahangiri, describe opulent court events and sumptuous gifts in great detail. They also reflect the emperor's intense interest in the natural world—most evident in the meticulous descriptions of the plants and animals he encountered in India and during his travels. Jahangir is notable for his patronage of botanical paintings and drawings. In addition to works made at his own court, botanical albums with beautifully drawn and scientifically correct illustrations were brought to India by European merchants (see fig. 33). These inspired many of the works in Jahangir's court.

Emperor Shah Jahan's court was unrivaled in its luxury. Like his father Jahangir, Shah Jahan (fig. 30) also had a strong interest in the natural world and a taste for paintings, jewel-encrusted objects (fig. 31), textiles, and works of art in other media. In spite of his large collection of portable works, Shah Jahan is best known for his architectural commissions, which include a huge palace in Delhi and the Taj Mahal (fig. 28), a mausoleum built for his favorite wife. Shah Jahan's architectural projects also reflect the Mughal love of botanical imagery; many of the Taj Mahal's walls are carved with intricate images of recognizable flowers and leaves (fig. 32).

Fig. 30. Shah Jahan on a Terrace, Holding a Pendant Set With His Portrait: Folio from the Shah Jahan Album (recto) (detail), dated 1627–28; artist: Chitarman (active about 1627–70); India; ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; 15 5⁄16 x 10 1/8 in. (38.9 x 25.7 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, 1955 (55.121.10.24)

Fig. 31. Mango-shaped flask, mid-17th century; India; rock crystal, set with gold, enamel, rubies, and emeralds; H. 2 1/2 in. (6.5 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 1993 (1993.18).

This small flask typifies the Mughal interest in natural forms and their transformation into richly decorated objects. The realistic mango shape was carved from rock crystal and encased in a web of golden strands of wire punctuated by rubies and emeralds. This flask is a practical vessel—possibly used to hold perfume or lime, an ingredient in pan, a mildly intoxicating narcotic popularly used in India—as well as a jewel-like decorative object that would have displayed the wealth and refined taste of its owner.

Fig. 32. Detail of wall showing highly naturalistic floral decoration, Taj Mahal, Agra, India, 1632–53.

During the golden age of Mughal rule (approximately 1526–1707), the emperors had a marked interest in naturalistic depictions of people, animals, and the environment. They employed the most skilled artists, who documented courtiers and their activities as well as the flora and fauna native to India. Informed by Mughal patronage, a new style of painting emerged in illustrations made for books and albums, which combined elements of Persian, European, and native Indian traditions. These works demonstrate keen observation of the natural environment and the royal court. The emperors collected their favorite poetry, calligraphy, drawings, and portraits in extensive albums, which were among their most valued personal possessions and were passed down to successive generations.

In addition to works on paper, the decorative arts of the Mughal court engaged a broad range of natural forms in carpets, textiles, jewelry, and luxuriously inlaid decorative objects, and used precious materials ranging from gemstones and pearls to silk.

| Previous Section | Next Section |