The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its first building in Central Park nearly 140 years ago. The institution has since grown to become a microcosm of a city, encompassing nearly 2.1 million square feet spread across 21 buildings. It has been incumbent on each generation of Museum leaders to steward this collection of buildings at The Met Fifth Avenue—and its sibling, The Met Cloisters—ensuring that the edifice not only meets the changing needs of the City but proposes by way of example a viable future for posterity.

Today, The Met is on the cusp of the most impactful changes to its campus since the completion of its current footprint in 1990. With a capital projects program that is poised to invest nearly $2 billion in the local economy in the next two decades, The Met will determine the relevance of cultural institutions as economic engines that can directly address climate change and socioeconomic inequity in real, quantifiable ways. With a dwindling middle class and a corresponding increase in social tribalism, coupled with a global rise in temperatures, the stakes are indeed high.

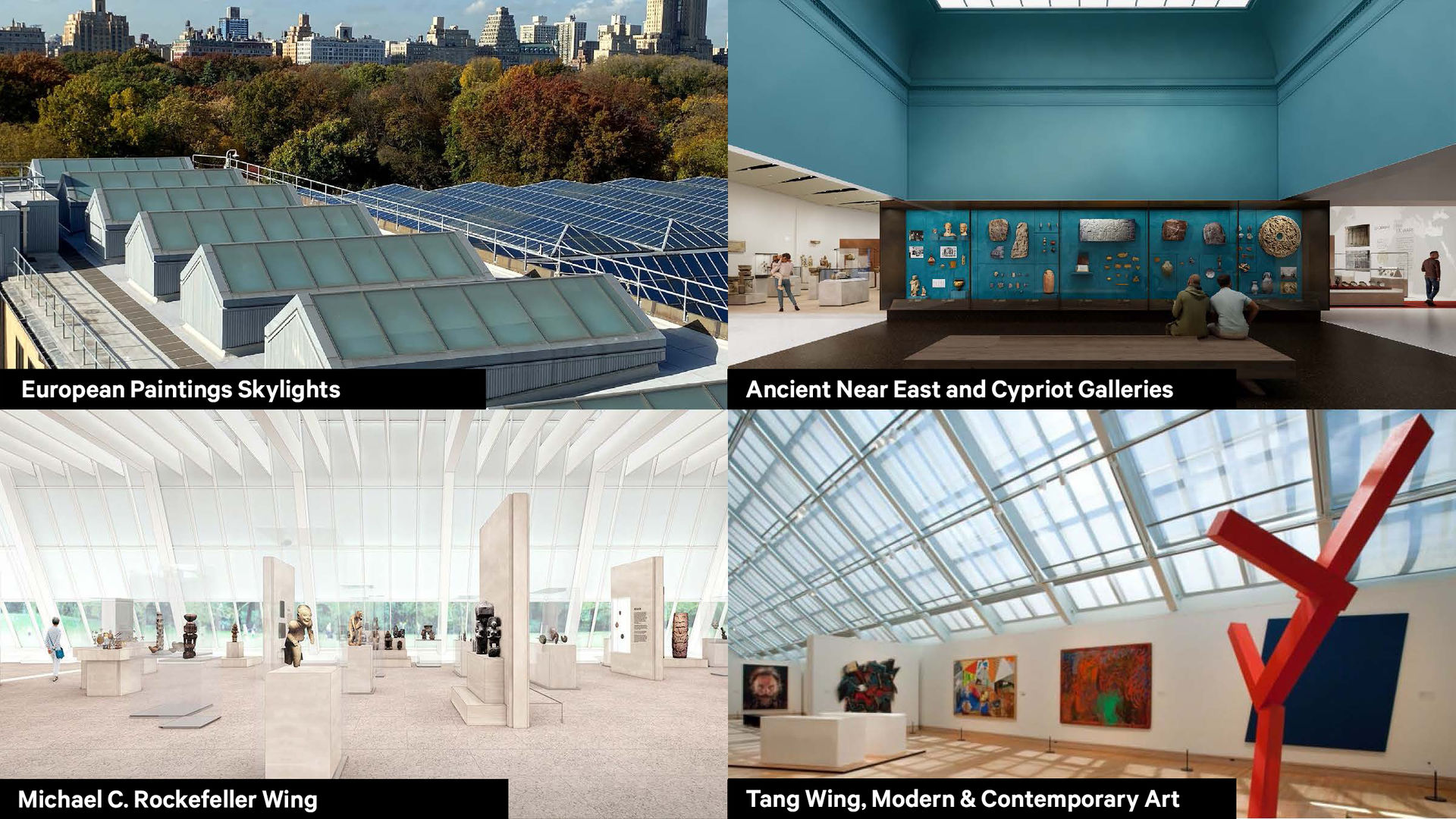

Four significant projects, among a portfolio of dozens, will drive this meaningful and ambitious work: construction of a new 125,000-square-foot modern and contemporary wing (the Oscar L. Tang and H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing); the renovation of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, spanning 40,000 square feet of redesigned galleries for the arts of the ancient Americas, Oceania, and Africa; 30,000 square feet of skylight replacements for the European Paintings galleries; and 15,000 square feet of re-envisioned galleries for the Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art collections. Alongside these major interventions, there is a new central chiller plant underway at The Met Fifth Avenue, the implementation of geothermal technology at The Met Cloisters, a new children’s learning space for our Education program, and a comprehensive rethinking of the Museum’s 300,000 square feet of office space.

Major projects currently underway

Though wide ranging, these projects are not isolated events. Rather, they are united by our core values and informed by the desire to wield the edifice (of which we are merely tenants) as a tool for socioeconomic progress prioritizing local resources, resiliency, renewable energy and materials, job creation, living wages, workforce training, and technology incubation. The act of building requires engagement with these issues, and our capital projects should proactively assist with the reconstitution of our middle class—the foundation of a functional democracy. Our partnership with both City and State officials is paramount, as they marshal resources and policies toward the same end.

Our ambition to join this cause is neither a distraction nor at odds with our role as a cultural institution dedicated to the preservation and exhibition of art. The Met’s founders envisioned our museum as a resource for New York’s community of craftspeople and makers—a place where the “working millions” could come to learn and understand their own work as elementally related to the masterpieces of human ingenuity and craft on display. What, then, are our galleries if not prisms that shift our gaze and reverence toward the act of making? Our collections are a testament to labor and provide the inspiration needed to see the people who construct our galleries and improve our infrastructure as artisans, whose work will one day be the subject of study by the art historians of the future. Our recent exhibition of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photographs, which carefully memorialize overlooked buildings and infrastructure, attests to the built environment as a socially significant endeavor of collective imagination that mediates and transforms our place in the world.

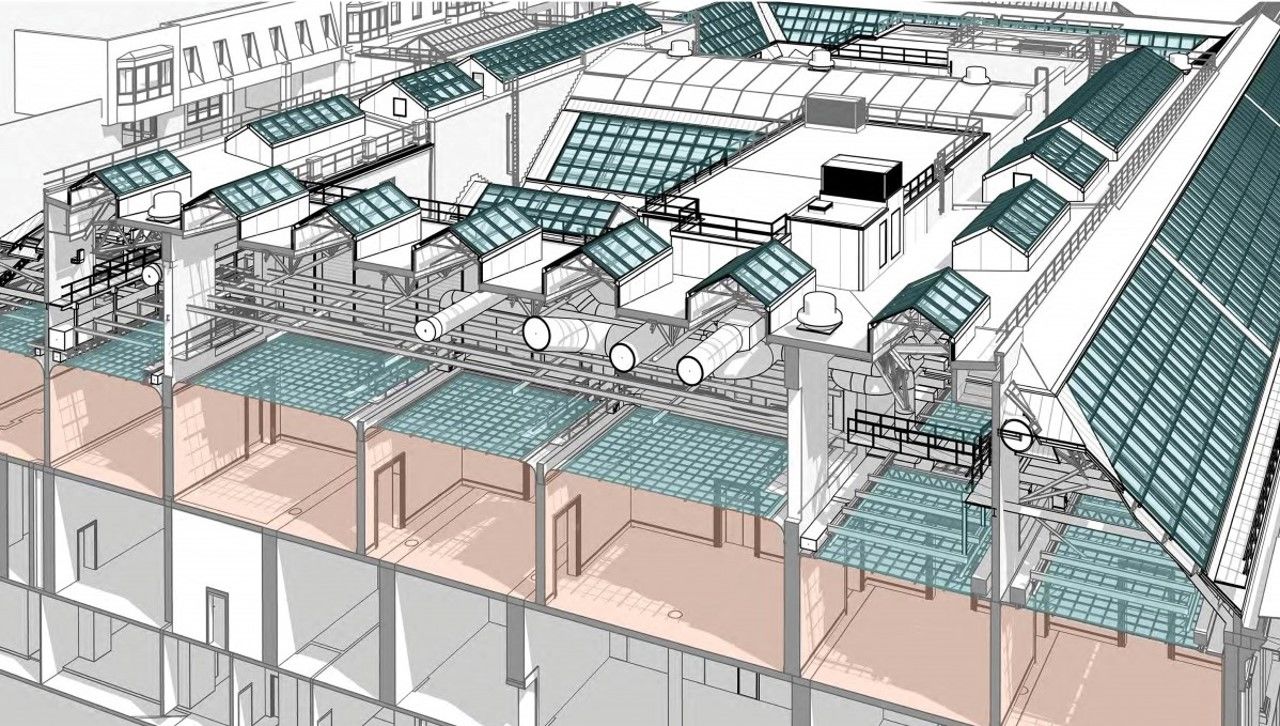

European Paintings Skylights by Beyer Blinder Belle, Kohler Ronan, Arup, WJE and Skanska

If the skylights project teaches us the peril of decoupling infrastructure from the galleries, the galleries themselves provide an opportunity to mine contemporary acts of making to deepen our understanding of our collections while engaging with climate change and socioeconomic inequity in quantifiable ways.

One of the first, critical decisions we make is the commissioning of an architect sympathetic with our values. During the last 18 months, we have selected Frida Escobedo for the modern and contemporary art galleries and Nader Tehrani, along with Moody Nolan, for the Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art galleries. As a by-product of these engagements, we have far surpassed City and State recommended fee percentages allocated to minority- and women-owned business enterprises (MWBE), reaching 45% and 75% on the Tang Wing and Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art galleries, respectively.

However, these commissions were not based on meeting quotas but rather on identifying architects who engage aesthetics at the level of the supply chain and whose architectural interventions aim to be didactic and that resonate with our collections. Though the full impact of these projects as engines of economic development will not be fully realized until construction begins, the design for the Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art galleries is far enough along to anticipate its impact. Tehrani’s propensity toward the innovative use of materials and details as catalytic shapers of space foreshadows a series of galleries that will create a resonance between contemporary artisanal techniques and those represented in the collection. Tehrani’s approach aligns with a Mesopotamian framework whereby beauty is conferred through the mastery of craft; beauty is not determined by personal taste.

Rendering, Ancient Near East & Cyprus Galleries by NADAAA, with Moody Nolan

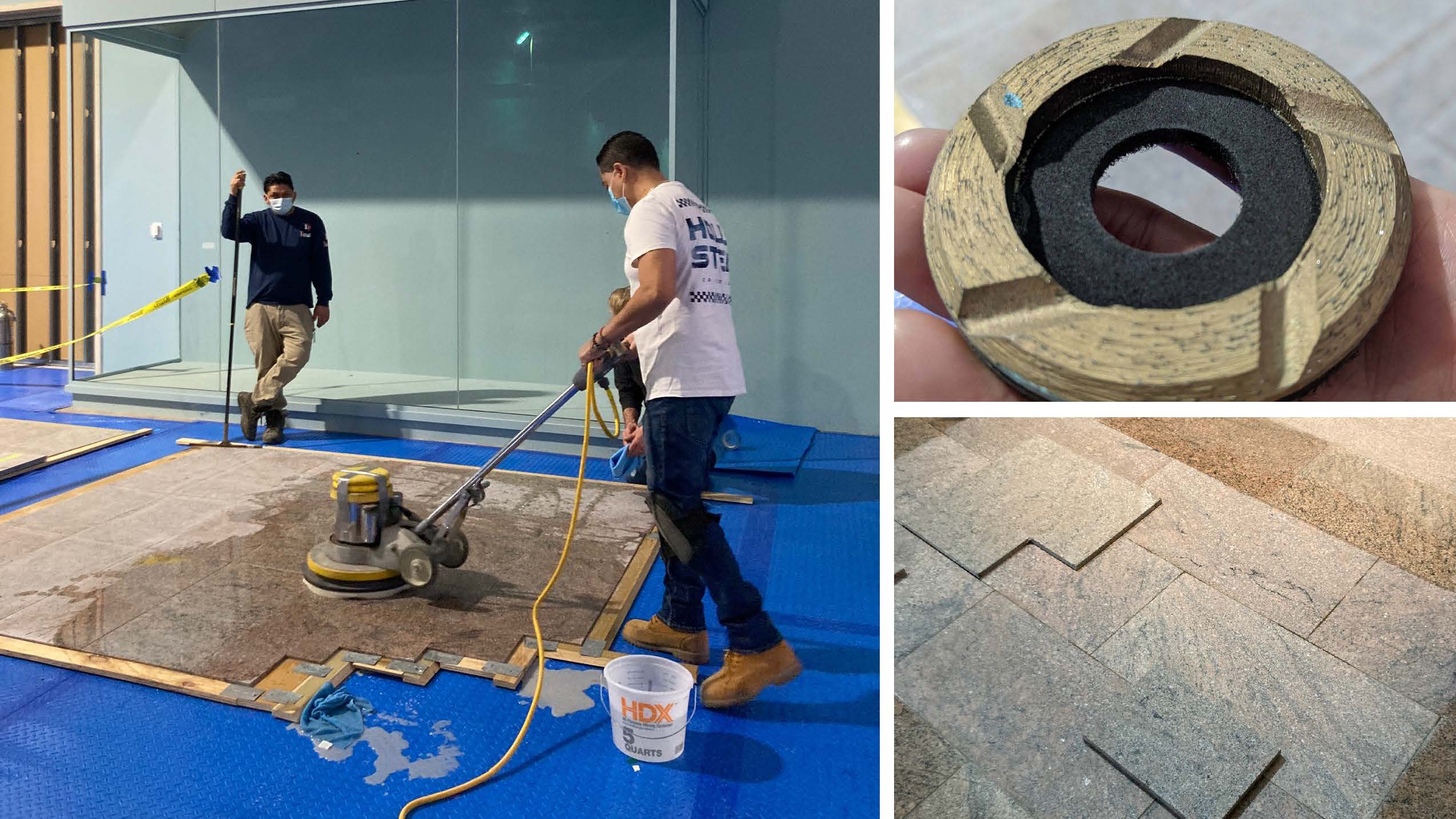

If the Ancient Near Eastern and Tang Wings remain in the realm of untested propositions, the redesigned 40,000-square-foot Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, deep in construction, is proof of concept. Our decision to retain and transform the existing Stony Creek granite floor elevates discussions of aesthetics by meaningfully engaging with issues of economy, sustainability, artisanship, and technology. We worked closely with our community of artisans—WHY Architects (Kulapat Yantrasast), Beyer Blinder Belle, AECOM/Tishman, and their trades—to develop a specialized mechanical abrasion process that transforms the high-honed stone surface into a color and texture akin to its natural state in the ground. As a result, we have created an entirely new specification for Stony Creek granite, now referred to as “The Met spec” by the quarry—a significant innovation, given its 170-year-old history. Perhaps more importantly, retaining the existing floor reduces the carbon footprint of the project by 81,000 kilograms, equal to the carbon produced by burning 90,000 pounds of coal, which would require 100 acres of forest an entire year to sequester.

Transformation of the Michael C Rockefeller floor

But it is the potential relevance of the floor beyond The Met that is most exciting. Stony Creek granite is present at many important and iconic democratic spaces in New York City, including the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, and Central Park, as well as institutions such as Columbia University. As aesthetic tastes change, materials are often discarded in favor of new trends; this can be a terribly wasteful process. Instead of scrapping the Stony Creek granite, we altered our understanding of the material’s capacity to change. The floor’s transformation is a road map for other institutions aspiring to develop ethical frameworks for aesthetic decisions—“the ethics of aesthetics,” as we say at The Met. Most profoundly, the transformation took its cue from the collection itself—specifically, a Sahelian (Sahel is a region of North Africa) process that continually renews the relevance of existing structures by altering its surface through the addition of material. We’re reminded, then, of The Met’s power to focus our actions on contemporary practices that engage with the most pressing issues facing humanity.