As an intern at The Met in 2021—a year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and one of the most tumultuous years of my life—I cannot help but look back to historic global calamities and consider how art has both responded to and survived from them. My mind travels to the 1930s and the economic collapse known as the Great Depression, which affected all facets of American life. To respond to such pervasive changes in the country, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his administration launched a large-scale initiative called the New Deal that aimed to alleviate economic strains and move toward social reform and justice. One of these programs was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which employed millions of Americans to work on public projects such as infrastructure and, quite significantly, gave support to artists, writers, and musicians through an initiative called the Federal Arts Project (FAP).

Even The Met, I was surprised to learn, received aid through this program. Dozens of WPA staff members supported the Museum by leading lectures, installing artworks, and illustrating works for various publications. Though the Depression-era program ended after American intervention in World War II, we can see the echoes of the FAP’s efforts through the drawings, prints, and other art works that remain in The Met’s collection to this day.

Theodore Roosevelt High School (The Bronx, New York): Arms and Armor (opened February 9, 1939); With teacher and students visiting the exhibition. Photographed February 1939

During my internship in the Department of Drawings and Prints, I explored works spanning multiple centuries and observed how they reflect the social contexts of the eras in which they were made. Important Black American artists and their contributions to the FAP were of particular interest. Not only did the FAP emphasize the importance of artists by providing them with employment through the government, but it also gave Black artists access to resources and opportunities that were previously unattainable. When thinking of figures who were able to redefine what American art meant in the 1930s and 1940s, Dox Thrash (1893–1965) is critical.

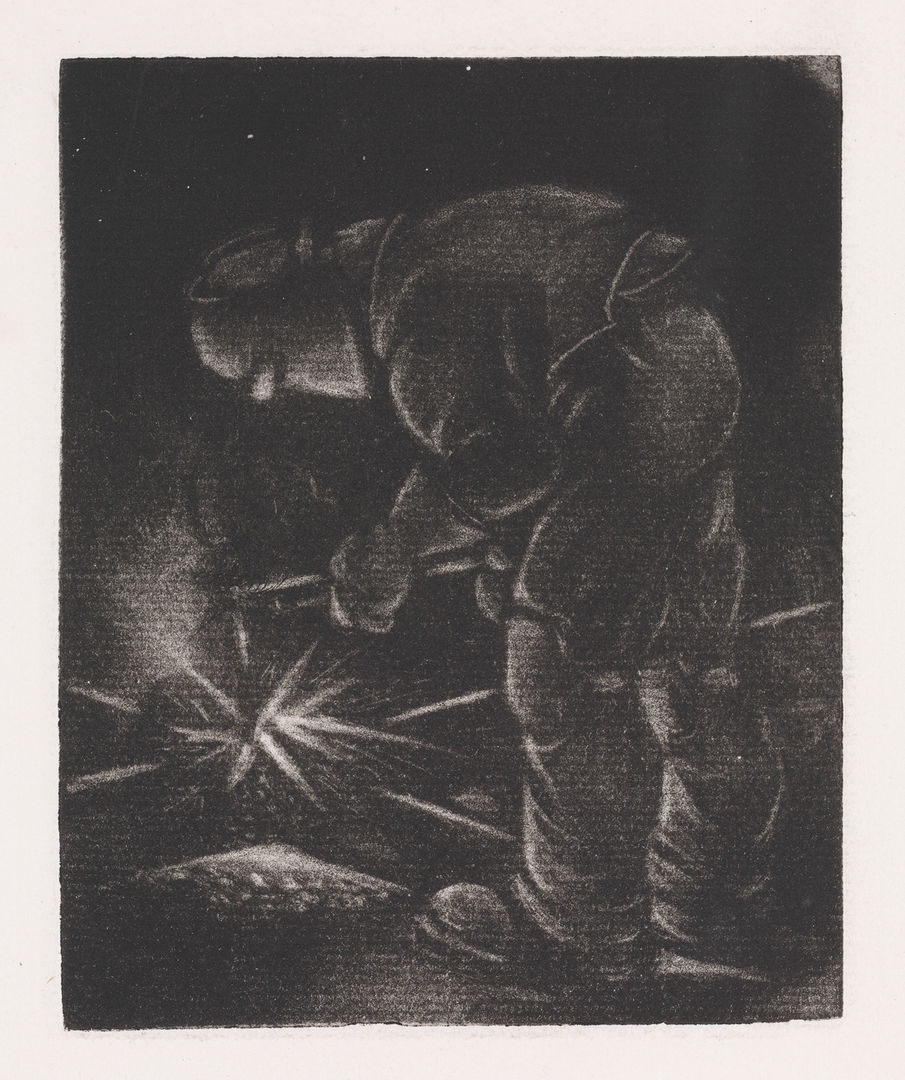

Thrash was a painter, printmaker, and art instructor who worked for the FAP in Philadelphia in the late 1930s. While working for the FAP, he co-invented the carborundum printing process, a technique which he coined as “Opheliagraph” in homage to his mother, Ophelia. To create a carborundum print, Thrash abraded a metal printing plate with the industrial material of carborundum. Working from dark to light, he burnished, or smoothed, the rough surface to form his composition. Thrash’s work centers around Black identity and the urban industrial landscape, underscoring the presence of collective labor during this period.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). The Welder (ca. 1936–41). Carborundum mezzotint, 10 × 6 in. (25.4 × 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 1999 (1999.529.167)

Thrash’s print The Welder (ca. 1936–41) portrays a laborer engulfed in darkness and shielded by a mask as sparks fly from a torch. Not only does this medium showcase Thrash’s impeccable printmaking technique; it also highlights a profession that requires intense manual labor that is often unseen and underappreciated. Thrash’s subject highlights how the FAP provided a platform for artists, who were also in previously under-supported occupations, and represents the eclectic and egalitarian nature of the program.

—Nayeon Park

The WPA was an essential component of Roosevelt ’s New Deal, especially considering that the unemployment rate reached twenty-five percent at its height. Roosevelt believed that art created by many people would boost morale and give the public hope during a period of unprecedented economic collapse. The WPA was largely nondiscriminatory in terms of race and employed over 350,000 Black Americans, fifteen percent of its total workers. Though many great artists worked for the FAP, Charles Henry Alston was particularly interesting to me. Alston was an influential painter during the Harlem Renaissance and was the first Black American artist to hold the title of supervisor under the FAP. Alston was inspired by the Mexican muralists who focused on social activism, which can be seen in a lot of his work.

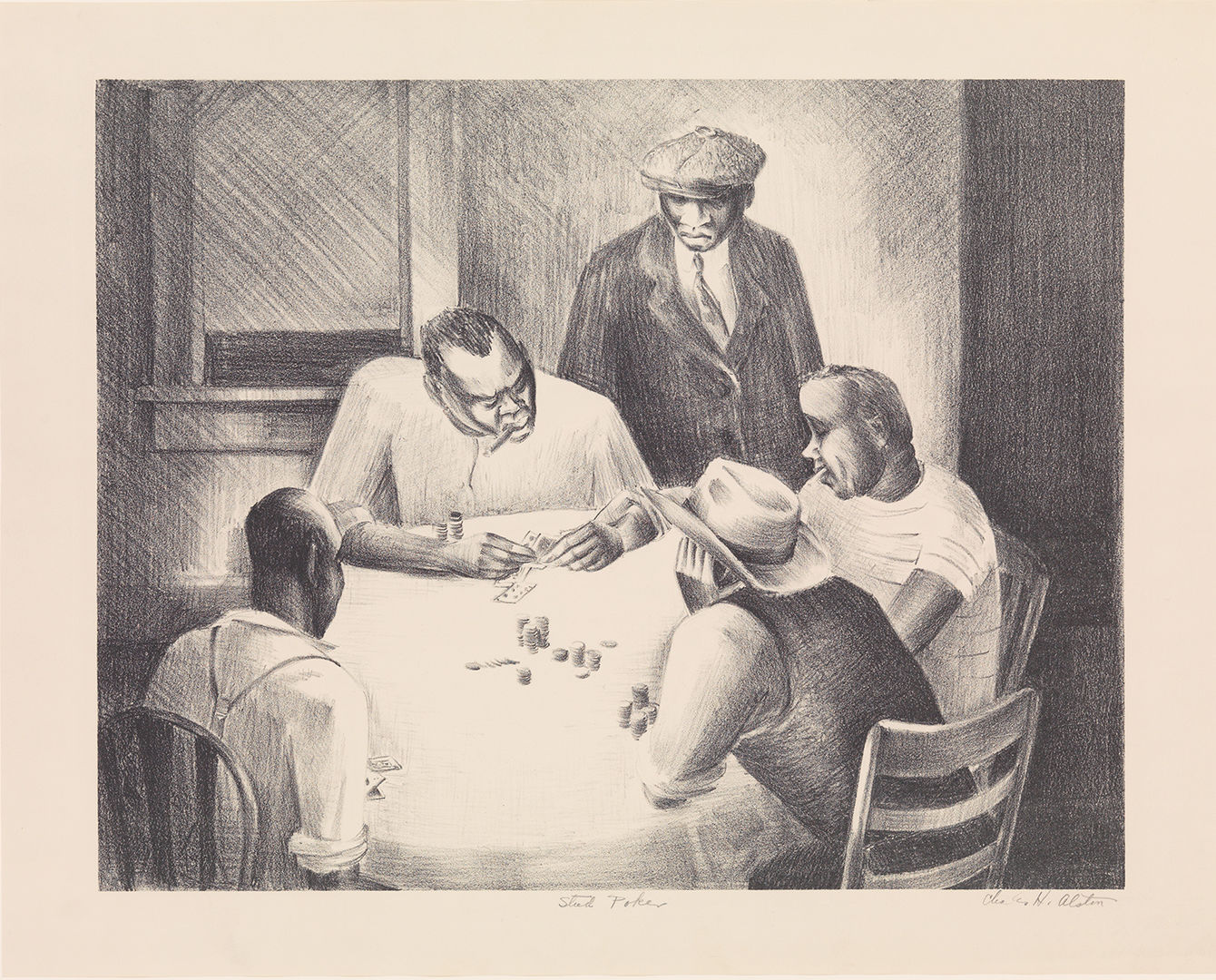

Charles Henry Alston (American, 1907–77). Stud Poker (1938). Lithograph, 15 5/16 × 19 1/8 in. (38.9 × 48.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City WPA, 1943 (43.33.730)

One print of Alston’s that caught my attention was Stud Poker (1938), which was gifted to The Met by the New York City WPA. The lithograph shows five Black men sitting around a small table playing poker. Alston intimately captures a moment of normalcy for these men. During the Depression, many drawings only depicted hardship. I admire that Alston took a different approach and showed these men outside the realm of life’s struggles as ordinary people. His use of details also indicates that he wanted the men to be the focus of the print. For example, the background does not contain many details, whereas the men’s faces, the playing cards, and the poker chips are highly complex.

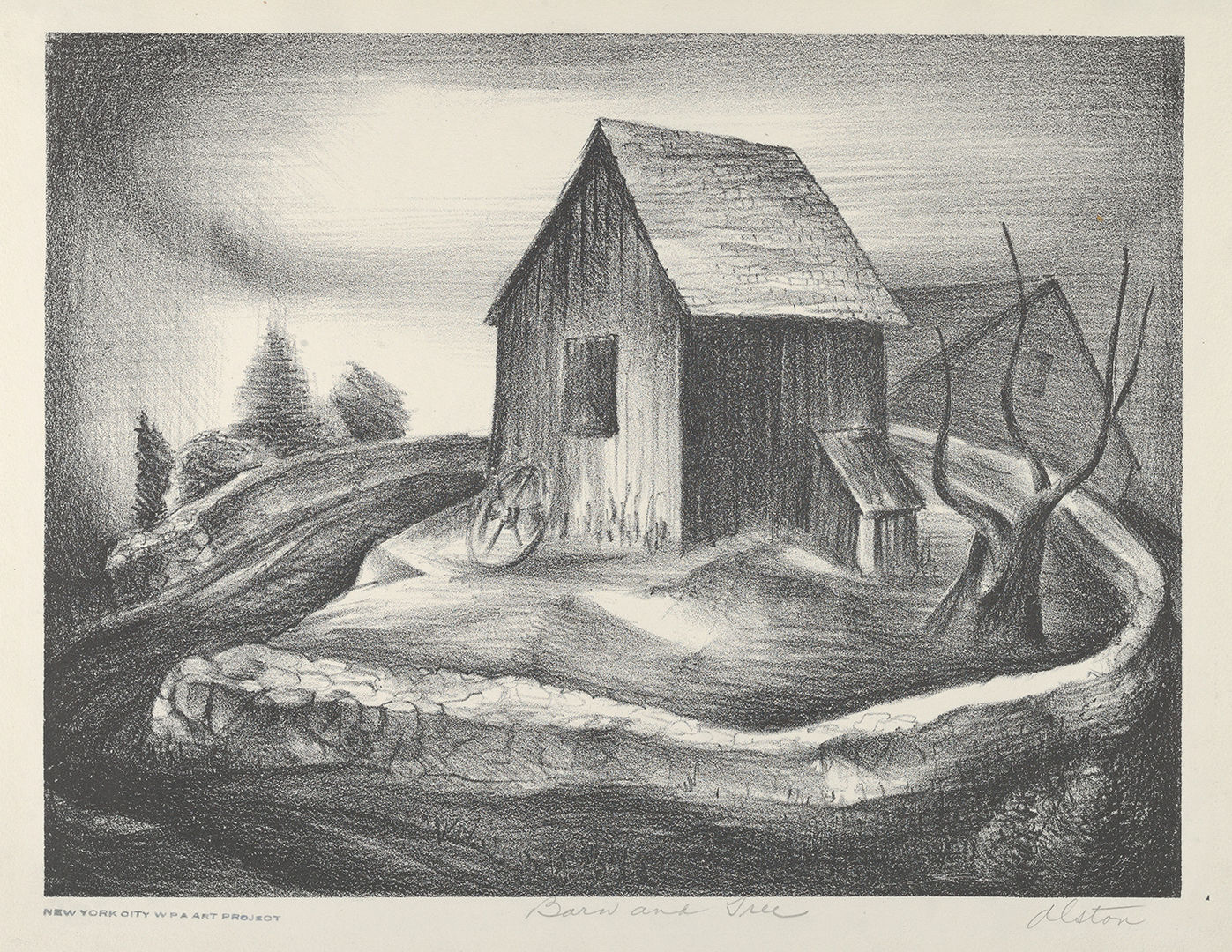

Another compelling work by Alston is Barn and Tree (1934). Unlike the light atmosphere in Stud Poker, this image has a much darker mood. Using a semi-warped perspective, Alston presented the barn sitting on a hill. A group of trees in the background are covered in leaves; by contrast, the tree to the right of the barn is dead and barren. From this, I infer that perhaps Alston had a bad connection to the things that happened on this site, possibly having to do with racial violence in rural America. Alston once again does not engage traditional realism here, as we can see in the brushy ways in which he depicted the leaves on the trees in the background and the grass in the foreground.

Charles Henry Alston (American, 1907–77). Barn and Tree (1934). Lithograph, 11 1/4 × 14 1/4 in. (28.6 × 36.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City WPA, 1943 (43.33.564)

When I attended high school in Harlem, I experienced art daily: almost every street has a mural, and there was always music playing. I believe this is a legacy of the WPA as many Black artists worked in Harlem to create these murals, and it is stimulating to see their work delight passersby many years later.

— Sabrina Bekirova