In the spring of 1779, the painter Richard Cosway exhibited a portrait depicting Marianne Dorothy Harland, the daughter of a British vice admiral, at London’s Royal Academy. The painting shows Miss Harland in her dressing room, playing the harp while a lapdog sleeps at her feet. The sitter occupies a fashionable interior that contemporaries would have recognized as a private feminine space through such features as the dressing table bearing a pincushion, scent bottles, and powder puff, objects associated in eighteenth-century Europe with the grooming rituals of elite women. Miss Harland’s clothing, a white morning dress and mantle, indicates that her hair has just been arranged and powdered.

Richard Cosway (British, 1742–1821). Marianne Dorothy Harland (1759–1785), Later Mrs. William Dalrymple, 1779. Oil on canvas, 28 x 36 1/8 in. (71.1 x 91.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. William M. Haupt, from the collection of Mrs. James B. Haggin, 1969 (69.104)

Because much of my research has centered around portraiture, gender, and sexuality, this painting, which has been at The Met since 1969, was of particular interest to me when my colleagues and I began the process of rethinking the Museum’s permanent galleries of European painting. One of my first steps in studying the portrait was to consult the Burney Newspapers Collection, a vast digitized archive of early British periodicals, to see if any contemporaries had responded to Cosway’s vivid evocation of an upper-class woman’s private rituals. Sure enough, I soon came upon these lines penned by an anonymous critic for the St. James’s Chronicle, who saw the portrait when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy:

The Portraits of this Artist [Cosway] are drawn with Precision, and finished with a painful and minute attention to little Circumstances. By these Means, a Bouquet of Flowers, or a Lady’s Ruffles, become the principal Object; and his productions acquire a coxcomical and ridiculous air.

Even by the standards of the eighteenth century, this seemed like a very harsh response to an innocuous painting of a young woman playing a harp in her dressing room. One clue to the reviewer’s objections came in the curious word “coxcomical.” Literally meaning a rooster’s crest, “coxcomb” has also been used since the sixteenth century to refer to vain and affected men, as in “an ass and a fool and a prating coxcomb” from Shakespeare’s Henry V. It often conveys a sense that the man in question deviates from traditional norms of masculinity, particularly by being overly invested in his appearance. The reviewer’s use of the word “coxcomical” suggests that he was troubled less by the painting than by the painter himself.

Richard Cosway (British, 1742–1821). Self Portrait, ca. 1770–75. Ivory, Oval, 2 x 1 5/8 in. (50 x 42 mm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Charlotte Guilford Muhlhofer, 1962 (62.49)

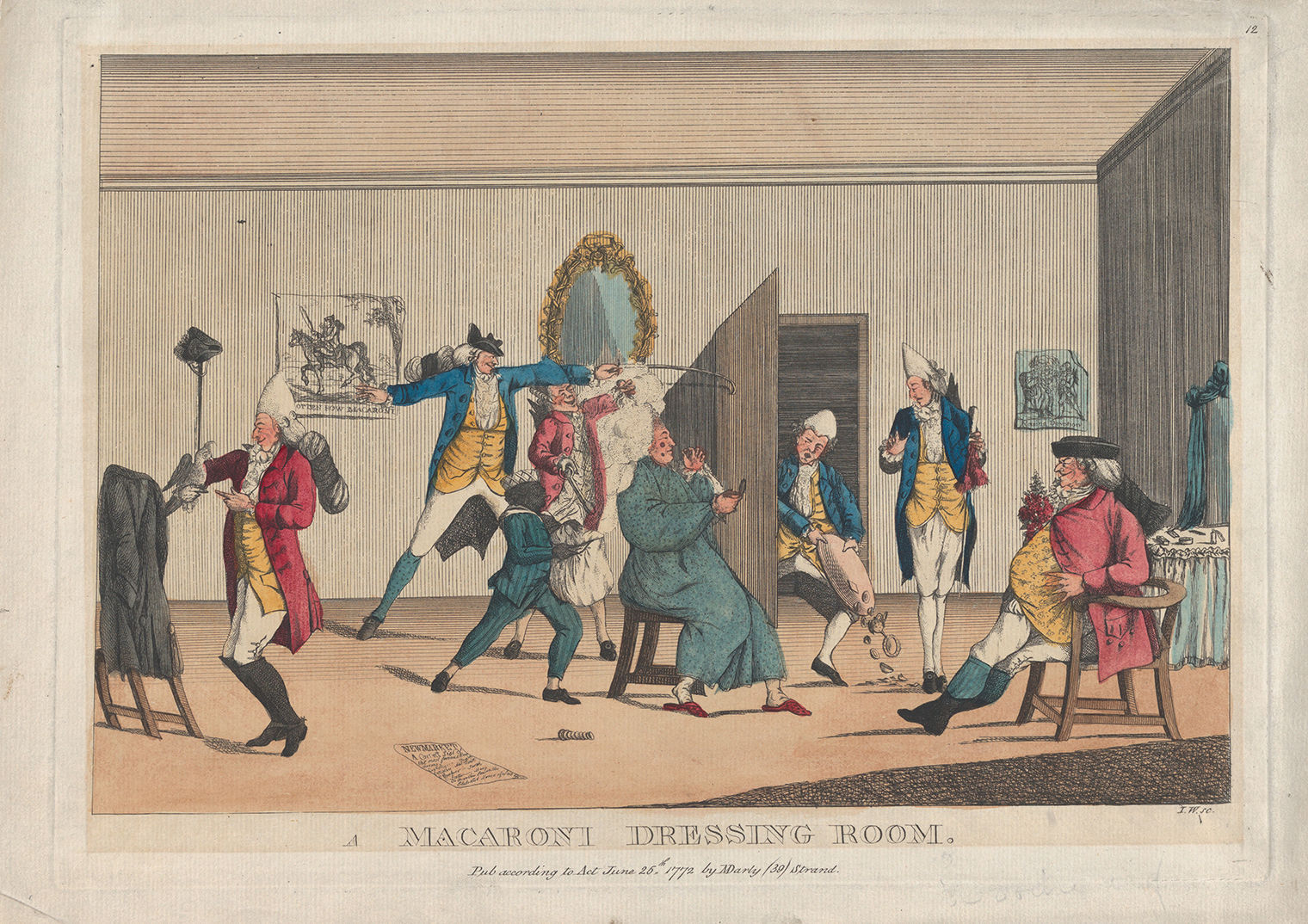

I.W. (British, active 1772) and Captain Minshull (British, active 1772). A Macaroni Dressing Room, 1772. Hand-colored etching, Plate: 9 13/16 × 13 7/8 in. (24.9 × 35.2 cm) Sheet: 10 3/4 × 15 3/16 in. (27.3 × 38.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1971 (1971.564.7)

Left: Richard Cosway (British, 1742–1821). Mrs. Robinson as Perdita, ca. 1779. Graphite, blue chalk, and watercolor, with touches of gouache (bodycolor), oval sheet: 7 13/16 x 6 in. (19.9 x 15.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Alexandrine Sinsheimer, 1958 (59.23.21). Right: Richard Cosway (British, 1742–1821). Lavinia, Countess Spencer as Juno, ca. 1806. Graphite, sheet: 12 5/8 x 9 3/8 in. (32.1 x 23.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George D. Pratt, 1935 (48.149.21)

Art historians have long celebrated painters like Peter Paul Rubens and Pablo Picasso for embodying cultural ideals of virility, both in their action-packed paintings and their romantic relationships with beautiful women. At the same time, the canon of art history has frequently excluded both women artists and male artists perceived to have “feminine” traits. I first became interested in this phenomenon while writing my dissertation on the seventeenth-century Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck. Many of the articles I read often compared Van Dyck unfavorably to his older contemporary and mentor Rubens, drawing on explicitly gendered language. For example, writing about The Met’s Van Dyck self-portrait in 1950, the curator Wilhelm Valentiner described the artist as “coquettish,” “carefully groomed,” “indefinite,” and “boneless.” He went on to write that “Van Dyck had neither the strength of character nor the intelligence of Rubens. Vanity—a fault unknown to the latter—is a sign of limited mentality. Beyond being a great painter he was little more than a man of wealth, pampered by courts and women.” These attitudes persist in the way the two artists are treated in the discipline of art history. While I took an entire graduate seminar devoted to Rubens, I can’t recall being shown a single work by Van Dyck during the course of my education, despite his prominence in many American and European museum collections.

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641). Self-Portrait, ca. 1620–21. Oil on canvas, 47 1/8 x 34 5/8 in. (119.7 x 87.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 (49.7.25)

Richard Cosway, who lived more than a century after Rubens and Van Dyck, was fascinated by both artists, copying and collecting their works. (He even claimed to own Rubens’s paint box.) In his own time, Cosway’s transgressive fashions made him a figure of both fascination and mockery. One contemporary biographer described him as “ridiculously foppish… with a small three-cornered hat on the top of his powdered toupée, and a mulberry silk coat, profusely embroidered with scarlet strawberries.” Cosway’s critics projected their hostility toward his gender nonconforming persona by describing his painting as overly meticulous, “painful and minute.” Notably, these were supposed defects that male critics also often perceived in the work of women artists.

As it happens, Richard Cosway was married to a famous woman artist, Maria Cosway. Born in Florence to British parents, Maria Cosway, née Hadfield, was celebrated as a prodigy in her youth. Although Richard discouraged her from selling her paintings following their marriage, Maria continued to exhibit fashionable portraits and serve as a cultural celebrity. In fact, reviewers often liked to pit husband against wife when they exhibited their paintings side by side. In 1787, for example, one writer declared, “[T]he Productions of Maria are much superiour to those of her Husband.” The Cosways had a famously open marriage—one of Maria’s lovers was Thomas Jefferson—which further contributed to perceptions that both artists transgressed conventions around gender and sexuality. In a cruel theatrical satire about the Royal Academy published in 1786 by John Williams, alias Anthony Pasquin, Richard was portrayed as the character “Tiny Cosmetic,” a foppish figure of ridicule, who proudly boasts that Maria has cuckolded him with the Prince of Wales.

“Artists who focused on fashion, elegance, celebrity, and femininity continue to be taken less seriously than those who depicted naval battles or the deaths of heroic men.”

Pasquin’s vitriol toward the Cosways reflected a desire both to humiliate them in print and to exclude their art from serious consideration. In the more than two centuries since he wrote, a more decorous but equally dismissive attitude on the part of many art historians has marginalized both Cosways within the canon. Artists who focused on fashion, elegance, celebrity, and femininity continue to be taken less seriously than those who depicted naval battles or the deaths of heroic men. Fortunately, a major exhibition held at Scotland’s National Portrait Gallery in 1995 laid the groundwork for a rediscovery of Richard and Maria Cosway.

Nevertheless, at the time I began researching Cosway’s portrait of Marianne Dorothy Harland, the painting had languished in storage for years under a disfiguring layer of yellowed varnish. (The Met has no paintings or drawings by Maria Cosway in its collection, part of a larger pattern, now gradually being corrected, of neglecting the work of women artists.) I was delighted when Conservator Dorothy Mahon agreed to clean the painting, making the charm and delicacy of Cosway’s brushwork obvious once more. When the European paintings galleries reopen in November 2023, Cosway’s portrait will take pride of place in a gallery of eighteenth-century French and British depictions of fashionable life.